Blow Up (Trading)

What Is Liquidation? Why Does Liquidation Occur in Trading?

Liquidation refers to the forced closure of a leveraged or derivative position when losses have depleted your margin to near the minimum threshold. To prevent your account from going into debt, the system automatically closes your position. This typically happens with leveraged products like perpetual contracts and futures.

Margin acts as a “security deposit”—you use a small amount of margin to control a much larger position. Leverage is the multiplier for your position size. For example, 10x leverage means you control a $1,000 position with only $100 in margin. If the market moves against you, losses are calculated based on the full position size, first consuming your margin. When your margin is insufficient to maintain the position, liquidation is triggered.

How Does Liquidation Work? What Triggers Liquidation?

Liquidation is determined by the “mark price,” not the latest transaction price. The mark price is a reference calculated by the exchange based on index prices and funding rates, designed to reduce manipulation and avoid errors from extreme trading prices.

The trigger logic is: when account equity (margin plus unrealized P&L) ≤ maintenance margin, the system initiates forced liquidation. The maintenance margin rate is a minimum set by the platform for different risk tiers and relates to position size.

For example: If you use 100 USDT as margin and 10x leverage to open a long position worth 1,000 USDT, and the maintenance margin rate is 0.5%, your maintenance margin ≈ 5 USDT. If the mark price drops and unrealized losses approach 95 USDT (100 initial margin − trading fees − maintenance margin), the system will forcibly close your position. The actual liquidation threshold may be affected by fees, funding rates, and risk tier settings.

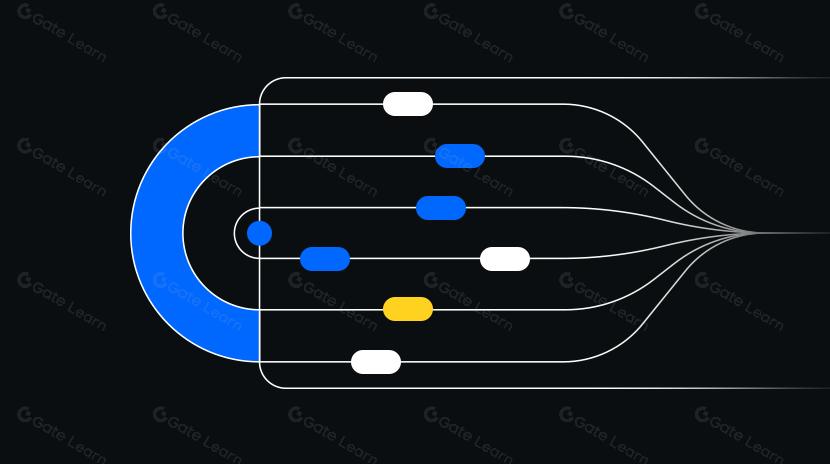

The forced liquidation process typically involves: attempting to close your position at market or limit price, using insurance funds to cover losses if available. If extreme market moves drain the insurance fund, Auto-Deleveraging (ADL) may occur—profitable traders’ positions are reduced to maintain overall risk.

What’s the Difference Between Liquidation and Stop Loss? Are Liquidation and “Forced Close” the Same?

The key difference between liquidation and stop loss is who makes the decision. A stop loss is set proactively by you to close a position at a planned price; liquidation is automatic and enforced by the system to prevent insolvency. Both limit losses, but stop loss offers more control—liquidation usually happens when risk management fails.

Terms like “liquidation,” “forced close,” and “margin call” are often used interchangeably in retail trading contexts. Technically, liquidation includes forced closure, use of insurance funds, and possibly ADL. Liquidation commonly refers specifically to the step where your position is forcibly closed by the system. Different platforms may use slightly different terminology, but all refer to automatic position management when margin runs out.

How Does Liquidation Work in Gate Contract Trading? How Do You Check Liquidation Price and Maintenance Margin?

In Gate contract trading, your position card displays key information such as “liquidation price,” “risk level,” and “maintenance margin rate.” The liquidation price is estimated by the system based on your leverage, fees, funding rate, risk tier, etc., and updates in real time as your position and market conditions change.

You can:

- In isolated margin mode, add margin to a single position, increasing your safety buffer and moving the liquidation price farther away.

- In cross margin mode, all contract assets share your total margin—profits and losses from other pairs affect overall liquidation risk.

- Review risk tiers: Higher-tier positions require higher maintenance margin rates, so liquidation can happen sooner.

Gate also offers take-profit/stop-loss orders, planned orders, and price protection tools to help you manage risk during market volatility.

Why Is Liquidation Common With High Leverage? How Does Leverage Relate to Liquidation?

Higher leverage means smaller allowed price moves against your position before liquidation occurs. Because losses are calculated based on total position size while your initial margin shrinks with increased leverage, liquidation becomes more likely.

A rule of thumb: Without accounting for fees, a 10x long position may be liquidated after about a 10% price drop; 5x leverage allows about a 20% drop; 3x about 33%. Actual thresholds vary due to fees, funding rates, risk tiers, and mark price formulas—these are rough estimates only.

That’s why professional traders often reduce leverage or position size during high volatility periods to increase their safety buffer.

Common Causes of Liquidation—How Do Funding Rates and Fees Affect Liquidation?

Main triggers for liquidation include:

- High leverage combined with sharp one-sided market moves that rapidly consume margin.

- Low liquidity leading to slippage, causing worse-than-expected exit prices.

- Mark price diverging from trade price, causing early forced closure during extreme market events.

- Funding rate costs accumulating over long-term positions, gradually eroding your margin buffer.

- Trading fees and frequent position adjustments increasing overall costs and sensitivity to liquidation.

Data trends: On highly volatile days in the first and second halves of 2025, total network-wide liquidations often reached tens of billions of dollars in 24 hours (Source: Coinglass, multiple statistics in 2025). This shows that rapid one-sided markets can trigger cascading liquidations and amplify volatility.

How Can You Reduce Liquidation Risk? Practical Steps on Gate to Avoid Liquidation

The core principle for reducing liquidation risk is to increase your “allowed adverse price move” space and make triggers more controllable.

Step 1: Use lower leverage. Dropping from 10x to 3–5x immediately expands the room for adverse market moves by several times.

Step 2: Set stop-losses and use planned orders. Place stop-losses before your liquidation price so you exit positions proactively rather than via forced closure.

Step 3: Use isolated margin mode and add extra margin when needed. In Gate’s isolated mode, adding margin directly increases your liquidation buffer without affecting other positions.

Step 4: Monitor risk tiers and maintenance margin rates. Larger positions may require higher maintenance margins—splitting or downsizing positions can enhance safety.

Step 5: Reduce position size or hedge during high volatility periods. Around major data releases or policy events, temporarily shrink positions or hedge with related instruments to lower one-sided risk.

Step 6: Factor in funding rates and holding costs. Long-term positions with positive funding rate costs continually eat away at your margin; switch to low-cost or neutral strategies if necessary.

Step 7: Use price protection and take-profit features. Price protection minimizes extreme slippage; take-profit locks in gains so you don’t give back profits near liquidation levels.

What Happens After Liquidation? How Does It Affect Your Account and the Market?

After liquidation, your position is closed by the system and remaining margin (after fees and slippage) stays in your account. In cross margin mode, other positions may also be affected; if extreme market conditions cause insolvency, insurance funds cover losses—if those run out, ADL can trigger forced reductions for profitable traders.

At the market level, mass liquidations create a “cascading effect”: forced sales drive prices lower, triggering further liquidations and amplifying volatility. This is why exchanges use mark pricing and tiered risk limits to mitigate chain reactions in liquidations.

Key Points & Risk Warnings About Liquidation

Liquidation is a core risk in margin trading—it happens when losses exhaust your margin buffer and positions are forcibly closed by the system. It’s determined by mark price and affected by leverage, maintenance margin rate, funding rate, trading fees, and liquidity. Sensible leverage choices, timely stop-losses, isolated margin adjustments, attention to risk tiers, and price protection can greatly reduce the chance of being liquidated.

Contract trading carries high risks; improper use of leverage can result in total loss of margin. On Gate, you should fully understand liquidation prices and risk levels before trading—build robust risk management plans suited to your risk tolerance, and always control positions carefully during major events or periods of high volatility.

FAQ

Where does my money go after liquidation?

After liquidation, your margin is used by the exchange to offset losses. The system first uses your margin to cover unrealized losses; when it’s insufficient for maintaining your position, forced closure occurs—any remaining funds (if any) are returned to your account. Essentially, what you put in gets consumed by market volatility; the exchange closes out your loss for you.

What leverage should beginners use to avoid liquidation?

Beginners are advised to start with 2–5x leverage. This way, even if markets swing 10–20% against you, you won’t be liquidated immediately—you’ll have time to react. High leverage (10x+) offers quick gains but exponentially increases risk; even small moves can trigger liquidation. On Gate’s contract trading, try a demo account first to understand liquidation risks at different leverage levels before using real capital.

If I see a liquidation warning but don’t stop out in time, will I be forcibly closed?

Yes—if you don’t manually stop out or add extra margin after seeing a liquidation risk alert, the system will automatically liquidate all relevant positions once the liquidation price is hit. This usually happens within seconds—you cannot intervene. That’s why it’s critical to stop out proactively while risks are still low; taking action yourself always results in smaller losses than forced liquidation.

Can multiple positions in one account affect each other’s liquidation risk?

Yes—all positions share your account’s available margin. A large loss on one position can drain margin and put other positions at risk of liquidation. For example: if you’re long BTC and short ETH simultaneously but BTC drops sharply and consumes your margin, your ETH short may also be forcibly closed. That’s why it’s important to manage overall account risk—not just individual positions.

Can I continue trading after liquidation? Will I need to repay losses?

You can keep trading with any remaining account balance after liquidation. If liquidation results in negative equity (insolvency), some exchanges may require you to repay losses—but Gate uses risk hedging mechanisms so insolvency is rare. Regardless, liquidation is an inherent contract trading risk; knowing the rules and setting stop-losses in advance is the best protection.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

What Is Copy Trading And How To Use It?